Thursday, September 26, 2013

Friday, September 13, 2013

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

Monday, September 2, 2013

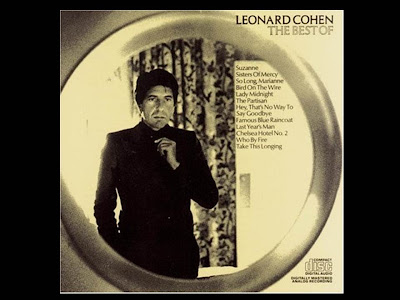

It doesn't matter which you heard....

In spite of my

previous familiarity with Cohen’s singing of his own Hallelujah, I had

no (or perhaps better said little knowledge) of the range of covers of that same

song.

Certainly I had

not seen Shrek (a blockbuster “spectacular,” as they say, of Hollywood

animation). In fine, I was as unaware of the many versions of the

Hallelujah song as many readers reading now might similarly suppose themselves

to be. What is at stake here is that this effective ignorance (be it a matter

of genuine non-knowledge or non-attention, and these are different things) is

also part of the exemplary and popular commonality of the Hallelujah Effect.

It

doesn’t matter, as Cohen would add in a later verse, which you heard and it

tends to be the case that no matter what one thinks one has heard some version

of it, whether one knows it or not.

As Bryan Appleyard emphasizes this point, you do know the song whether or not you recognize your own familiarity with it:

As Bryan Appleyard emphasizes this point, you do know the song whether or not you recognize your own familiarity with it:

Even if you think you haven’t heard it, I can guarantee you have. It has been covered by, among many others, Allison Crowe, k. d. lang, Damien Rice, Bono, Sheryl Crow and Kathryn Williams. Bob Dylan has sung it live in a performance that has, apparently, been bootlegged. It has been used endlessly in films and on TV. Rufus Wainwright sang it on the sound-track of Shrek, Jeff Buckley’s version was used on The West Wing and The OC, John Cale sang it on Scrubs and so on.[1]At the beginning of my own experience with the Hallelujah effect, and not being too, too much of a fan, be it of Cohen or anybody in the pop music world, I ‘liked’ Cohen’s Hallelujah — this is the Facebook-speak that has made “liking” more charged as conventional affect than it should be, and this remains true whether one substitutes a google+1 or a heart a thumbs up avatar or what have you.

[1] Appleyard, “Hallelujah! On Leonard Cohen’s Ubersong,” The Times, Sunday Times, 9June 2005. This is, indeed, among other things, part of Steven Lloyd Wilson’s “The Minor Fall, The Major Lift” along with a useful discussion of rhythm, illustrated in his own text with paratactically helpful interpellations.

(There is a whole yet-to-be-unpacked phenomenology of what one ought to call the Montessori effect: writing as a hands-on, whole body phenomenon. The appeal of the touch screen for the particular, relatively unfurred primates that we happen to be, and what using such buttons and restricted gestures does [or undoes] to our minds, would have to be part of that.)

Perhaps this was due to Cohen’s rhythmic delivery — I confess to a special weakness for his Who by Fire — perhaps this is just because I am fond of words, be it plainchant, spoken music, spoken poetry, word jazz — I spent my student years in Stony Brook and Boston listening to the great Ken Nordine (see link to the October 2012 edition of the Chicago Tribune)— and such and such.

But and at the same

time as I ‘liked’ Cohen’s song, it was also true that it was not my thing. I

could, as we say, take it or leave it.

That was that until

what I call dueling video-posts on Facebook.

But this dynamic is at work with other posts, like photos and like quotations from Woody Allen Esquire interviews --- as Sue Zemka, friends with Bob Frodeman says in response to the Woody Allen quote-thing Bob has going on as what she calls "an FB Facebook tear."

But this dynamic is at work with other posts, like photos and like quotations from Woody Allen Esquire interviews --- as Sue Zemka, friends with Bob Frodeman says in response to the Woody Allen quote-thing Bob has going on as what she calls "an FB Facebook tear."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)